October 6, 2023

Introduction

Like many Educational Service Agencies (ESAs) across the country, Appalachia Intermediate Unit 8 (AIU8) strives to create customized solutions to challenges that confront its member school districts. Fortunately, less than a year before the COVID-19 challenge arrived, the AIU8 embraced a state funding opportunity to collaborate with the nation’s only Trauma-Skilled™ Schools certification program to create a capacity-building model for addressing school trauma issues in its primarily rural, four-county region. The regional need and funding, model design strategy, model collaboration, and model implementation are described in this article. Additionally, observations of project successes, challenges, and lessons learned are described. A final section describes early stages of the model’s scale-up strategy to other ESAs by continuing the AIU8 and National Dropout Prevention Center (NDPC) collaborative partnership.

Collaboration theory is evolving, in its infancy, and not clearly understood (Morris & Stevens, 2016). In examining a 30-year period of literature on collaboration, Miller-Stevens and Morris (2016) conclude collaboration lacks definitional clarity, is often confused with cooperation and coordination, and needs much more investigation regarding why collaboration projects fail. Increasingly, collaboration is viewed as a key strategy in addressing and innovating solutions to critical educational challenges in rural areas (Harmon, 2017; Miller et al., 2017; Reardon & Leonard, 2018), including school leadership challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic (Johnson & Harmon, in press) and supports for students’ social-emotional and mental health needs (Nichols et al., 2017). Collaboration is essential for effective partnerships, an approach educational service agencies may use to address educational challenges (Polk, 2021). Numerous examples reveal the benefits of collaborative partnerships to improve the education and health outcomes for k-12 students (Kolbe et al., 2015).

Regional Need and Funding

Located in Altoona, PA, and one of 29 intermediate units in the state, AIU8 provides a vast array of services for member school districts, including services related to mental health and safe schools. The AIU8 service region includes four predominantly rural counties comprising 35 school districts (approximately 98 schools) and five Career Technical Centers. In the 2021-2022 school year, approximately 47,000 elementary and secondary students were enrolled in the 35 school districts.

In 2018-2019 monthly meetings and annual in-district interview sessions with superintendents, the AIU8 executive director learned of the increasing need for school safety and mental health services. AIU8’s coordinator of these services and associated staff confirmed the growing need and that both the Pennsylvania Department of Education (PDE) and the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency (PCCD) were increasing attention on school safety and mental health issues. In September 2019, PCCD released a request for applications for the School Safety and Security Grant Program. Eligible applicants (e.g., IUs) in the competition could apply for up to $450,000 for a two-year project.

The goal of the PCCD grant solicitation was to make school entities within the Commonwealth safer places. The grant required applicants to provide supporting data and facts, specific to the relevant problem, and noted data sources that could be used. Among the results reported in the PCCD School Safety Survey Findings, only 42.6% of districts in the state conducted the school climate survey. Moreover, only 7.6% of districts met the standard of one social worker per 250 students, or one per building of 250 or less students. Only 15.1% of districts met the standard of one counselor per 250 students. AIU8 personnel rationalized these findings were likely more severe in the AIU8 school districts, where access to social workers and mental health professionals was greatly limited because of availability in rural areas and/or cost.

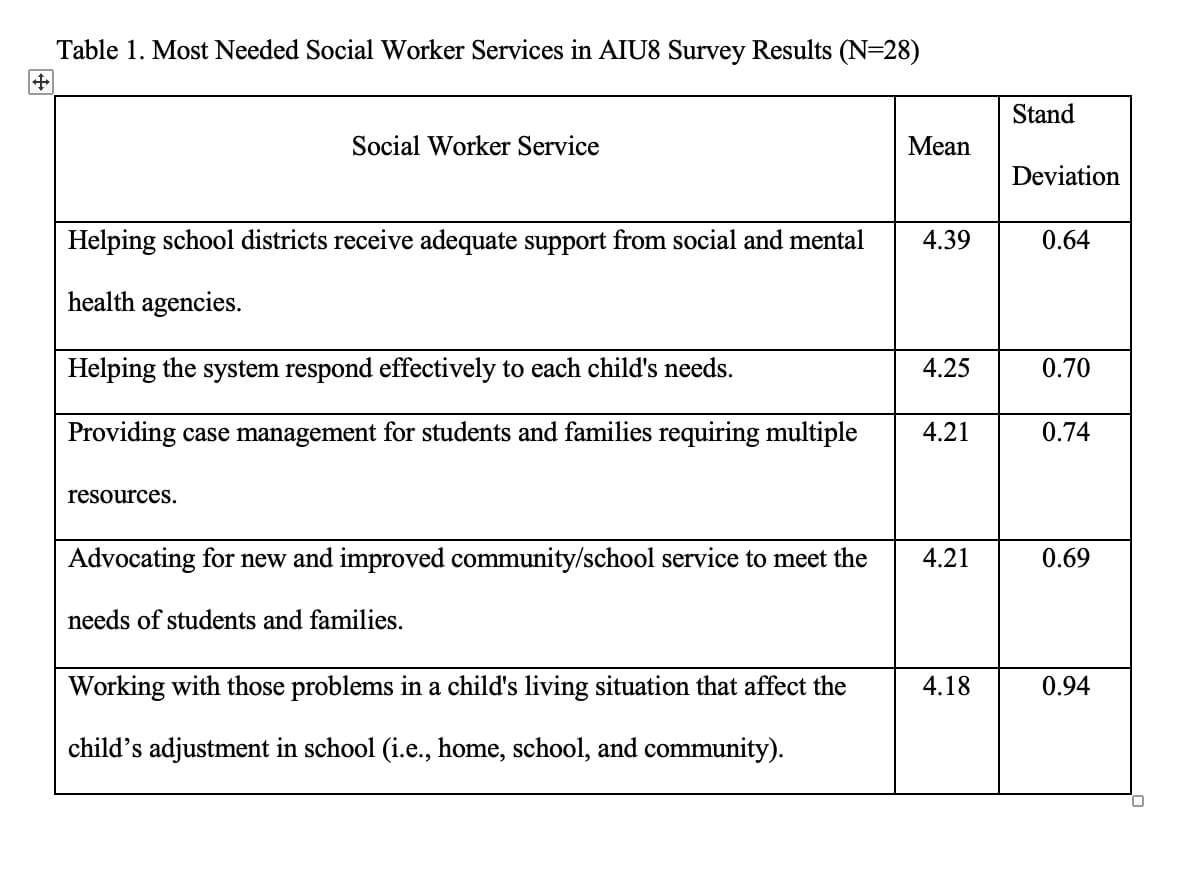

Consequently, project planners conducted an online Google Forms survey of the 35 school districts. Of the 35 school districts surveyed, 29 usable responses were received, representing 25 school districts. Superintendents comprised 14 of the respondents. Other titles represented by respondents included principal, school psychologist, school or guidance counselor, social worker, director of special programs, director of special education, and supervisor of student services. The survey included 29 services provided in schools as listed by the School Social Work Association of America (2012). Table 1 shows the top five “needed most” social worker services, as indicated by the 28 respondents who rated the 29 services using a scale of 1=Low Need to 5=High Need. Survey results showed the problem was schools in the AIU8 region had too little sustainable capacity of expertise and assistance to implement skills specifically aligned with trauma-informed interventions in their state-required plans.

AIU8’s grant planning team concluded school safety and trauma issues were interconnected. A focus on physical safety devices in school buildings with related planning and training would not provide an adequate solution to the needs expressed by superintendents. The region’s small rural school districts needed adequate sustainable capacity to help schools implement preventative safety-related practices that addressed the needs of trauma-impacted students.

Noting that addressing such needs were allowable expenses in the PCCD solicitation for applications, AIU8 also cited several studies in its grant application that emphasized increasing attention to school climate and teaching practices were essential safety prevention issues. For example, in analyzing every active shooter incident at a K-12 school since 1999, and creating a database back to 1966, Peterson and Densley (2019) found school shooters are almost always a student at the school, and they typically have four things in common: (1) they suffered early-childhood trauma and exposure to violence at a young age; (2) they were angry or despondent over a recent event, resulting in feelings of suicidality; (3) they studied other school shootings, notably Columbine, often online, and found inspiration; and (4) they possessed the means to carry out an attack.

Peterson and Densley (2019) noted that schools can do more than just upgrade security or have students rehearse for their near-deaths. Such activities are raising the anxiety levels of students, parents, and teachers. They noted a change in school culture is needed. Lockdown and active shooter drills send the message that violence is normal when it's not. Schools can instead plan to prevent the violence. To mitigate childhood trauma, for example, the researchers noted that school-based mental health services provided by counselors and social workers were needed.

A review of PA Student Assistance Program (SAP) data for the four counties in the AIU8 region revealed that the reasons for almost half of student referrals by school SAP teams were behavior concerns, family concerns, and social concerns. These reasons represented 47% of the 3,502 student referrals reported by SAP teams for the 2016-17 school year.

Model Design Strategy

Consequently, project planners designed a regional model that could build sustainable capacity in school districts, schools and the IU to address student trauma and related safety issues. A key component of the design included a collaborative arrangement with the Trauma-Skilled™ Schools Model (TSSM) offered by the National Dropout Prevention Center (NDPC). Of particular value was that the NDPC offered the nation’s only Trauma-Skilled™ Schools and Trauma-Skilled™ Specialist certification program—a Tier 1 program that moved educators beyond “trauma-informed” plans to “Trauma-Skilled™” practices. This collaboration and project design enabled AIU8 to be among the competitive grant winners announced by PCCD on February 26, 2020. AIU8’s two-year project, entitled the Trauma-Skilled™ School Safety Rural Network (TSSSRN), was awarded $449,945. The overall goal of the project was to build regional capacity for creating school climates that support student-centered practices and safer school environments.

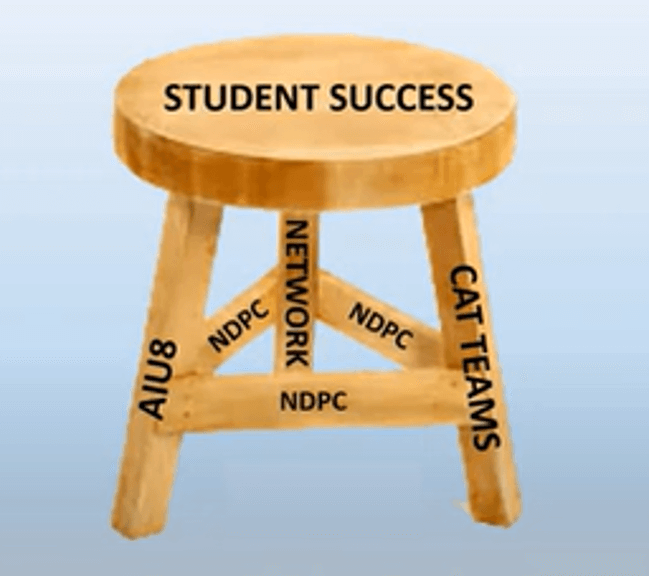

A three-legged stool strategy guided project design toward a collaborative capacity-building effort for the region (see Figure 1). The success of trauma-impacted students would be supported by establishing a catalyst action team (CAT), comprised of 4 or more staff members in each participating school district, by facilitating a virtual network for collaboration and sharing among the CATs, and by increasing expertise and technical assistance provided by AIU8. The National Dropout Prevention Center’s Trauma-Skilled™ Schools Model would reinforce each leg of the stool by providing training and technical assistance.

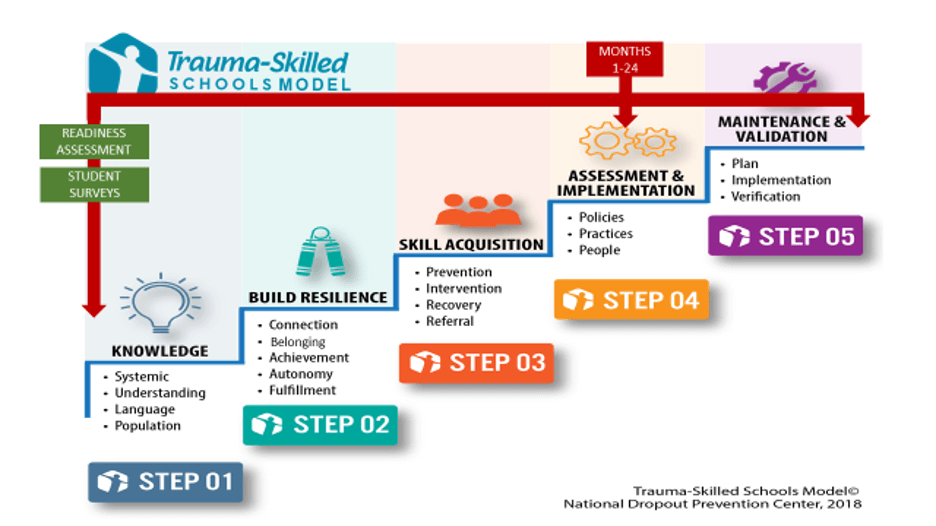

The NDPC created the Trauma-Skilled™ Schools Model in 2018 (Gailer et al., 2018). NDPC, now a division of the Successful Practices Network (SPN) established by Dr. Bill Daggett. The NDPC offers numerous training opportunities (e.g., institutes) and resources that support their certification models as a Trauma-Skilled™ School (TSS) and or a Trauma-Skilled™ Specialist. The TSS Model (see Figure 2) is a framework to help schools minimize the harmful effects of stress and trauma on learning, social development, and behavior by adjusting climate, culture, and practice across all areas of a school. The TSS Model is not a crisis prevention or intervention program. Nor is it clinical in nature. Rather, the TSS is implemented as a universal or tier 1 support. The TSS model is designed to meet the academic and social needs of all students whether they have experienced trauma or not.

The TSS model trains all school staff and offers a tier one level of support for all students that focuses on:

-

- Creating intentional shifts in school culture and climate

-

- Enhancing school safety

-

- Honoring the need for and supporting self-care strategies for school staff

-

- Supporting students by:

1. Infusing opportunities for emotional regulation (Purposeful Practices) by implementing Trauma-Skilled™ initiatives throughout school routines, and

2. Supporting the development of a custom Trauma-Skilled™ Schools plan that seeks to foster student resilience through implementing Trauma-Skilled™ initiatives that focus on student connection, belonging, achievement, autonomy, and fulfillment

In the NDPC TSS model, school personnel become Trauma-Skilled™ as they progress through the first three steps of the model. The first step is to acquire knowledge of the effects of stress and trauma and establish language to promote consistency in implementing the model. In the second step, school personnel learn to build resilience in students through fostering connection, belonging, achievement, autonomy, and fulfillment. In the third step, school personnel acquire skills necessary to prevent traumatic incidents, to intervene appropriately during traumatic incidents, to support recovery from such incidents, and, when necessary, to refer students to internal or external services properly. The final two steps of the model, assessment and implementation and maintenance and validation, are ongoing to ensure the model’s fidelity and assess the model’s impact (Gailer et al., 2018).

Moots (2021) analyzed results of the Trauma Skilled Readiness Assessment, a pre/post measure administered before school personnel begin TSS professional development and during the training stage prior to full TSS model implementation. Moots (2021) “identified increases in awareness of and knowledge about trauma-impacted students as well as progress in the development of educators’ resilience-building skills and abilities in all students, particularly those experiencing stress due to trauma” (p. 2).

In the AIU8 regional model, NDPC personnel first provide training for AIU8 personnel to understand the TSS model, use key resources/tools, and acquire specialist certification. Consequently, the AIU8’s capacity is increased to perform its critical collaboration role with the NDPC to ensure the catalyst action team (CAT) in each school district is established, trained, and supported with direct technical assistance. The logic model (see Figure 3) for AUI8’s PCCD-funded project reveals how inputs enable activities for each CAT and its members to acquire key capacity. AIU8 and NDPC personnel assist each CAT member in completing activities toward the TSS Specialist Certification. CATs then use the capacity to help their school(s) pursue the implementation of the TSS model. In addition, AIU8 personnel establish and facilitate the primarily virtual network, with the support of NDPC personnel. Through monthly, one-hour virtual network sessions, CAT members are able to clarify the requirements of TSS Specialists certification, plan and implement TSS model elements, and gain valuable insights from sharing experiences with each other.

As the logic model shows, the achievement of key outcomes is to result in the intended impact: safer schools in the region with the capacity to create school climates, resiliency, and supportive preventative practices for trauma-impacted students. The AUI8 program manager works with the project’s internal evaluator to establish a database to track implementation activities and outcomes. This supports the program manager and collaborative partnership team (i.e., AIU8/NDPC personnel) in planning topics for the CATs’ virtual network sessions and in providing in-person support to CATs in their school districts.

Model Collaboration

The AIU8/NDPC collaborative efforts focus on attainment of three capacity-building objectives:

-

- Create a district team with certified Trauma-Skilled™ members in all AIU8 school districts that chose to participate;

-

- Enable all teachers and staff in participating districts to complete Trauma-Skilled™ training; and

-

- Operationalize an AIU8 facilitated virtual support network for all participating district CAT members.

The AIU8/NDPC leadership team meets as necessary to develop and sustain an ongoing plan of action. Meetings focus on efficient strategies to support each objective. For example, to achieve objective 1, the AIU8 executive director announced during a monthly meeting of the AIU8 Unit Council (i.e., all district superintendents) the opportunity for each district to participate in the project at no cost thanks to the PCCD grant. After the NDPC TSS personnel provide a Trauma-Skilled™ Institute training to AIU8 core team members (comprised of AIU8 Program Manager and three AIU8 Educational Consultants), the AIU8/NDPC leadership team then held informational webinars (as COVID-19 had caused virtual meetings only) to explain the project and extend the invitation to participate. Originally, 16 districts chose to participate in year one. Four additional districts entered the project in year two.

Collaborative efforts continued as the AIU8/NDPC personnel supported each district in creating a Catalyst Action Team (CAT) comprised of at least 4 members, including district and school representation. In some districts, the superintendent is elected to serve on the CAT. The AIU8 created a series of Google Drive folders as a repository for CAT members to access training documents and other resources.

The AIU8/NDPC personnel collaborated to create a specialized path and process for CAT members to attain NDPC’s Trauma-Skilled™ Specialist Certification. The process included:

- CAT members completing Trauma-Skilled™ Institute Training presented by the NDPC.

- CAT selecting one targeted school building (or all schools in the district) for the team members to implement elements of the Trauma-Skilled™ Schools Model.

- CAT members submitting (to NDPC) a certification application with a written narrative component that describes the member’s personal and team Trauma-Skilled™ leadership efforts (as a measure of competencies attained).

- NDPC certification personnel reviewing (and approving or returning with recommended revision) the narrative component and providing the CAT member with a URL link to the NDPC Trauma-Skilled™ Specialist exam.

- CAT member completing Trauma-Skilled™ Specialist exam.

- NDPC scoring the exam, and if a satisfactory score was achieved, sending the CAT member a Trauma-Skilled™ Specialist Certificate with a request for a photo/bio to be added to the NDPC national database.

Key collaborative efforts that enable teachers and staff in participating districts to complete Trauma-Skilled™ training (objective 2) include:

- NDPC providing pre-training data collection survey tools (e.g., Trauma-Skilled Readiness Assessment), as well as personnel to analyze data and return aggregate data reports to the AIU8 team for return to the district CAT.

- AIU8/NDPC creating options for CAT teams to train at least 80% of staff in their targeted school(s), including how to use the Trauma-Skilled™ Schools Model workbook, access the video training series for the Trauma-Skilled™ Schools Model Steps 1, 2, and 3, and to provide or request post-training support sessions (called huddles) as needed.

- 3. AIU8 creating additional training resources (e.g., Milestone Tool; IU8 Staff Training Intro PowerPoint & Video) and five 1-hour supplemental online resource courses (one for each TSS Model resilience factor) for use by CATs to enhance training content/experience with schools.

Key collaborative efforts to operationalize the virtual support network comprised of and facilitated for all participating district CAT members (objective 3) include:

- AIU8 hosting in-person and or facilitating specialized virtual network monthly meetings with NDPC support assistance. (In response to COVID-19 safety mandates and protocols, some planned in-person activities were transitioned to a virtual format.)

- NDPC facilitating specialized virtual network monthly meetings for CAT members with AIU8 support assistance.

- AIU8/NDPC providing professional learning content (e.g., characteristics of effective teams, building staff collective efficacy) during network sessions to enhance implementation of the Trauma-Skilled™ Schools Model. In network sessions, CAT teams and individual members also had opportunities to share experiences, troubleshoot ideas, learn new strategies, and ask questions.

- AIU8 providing additional customized in-person and virtual support as needed to increase success of the district CAT (e.g., TSS Readiness Assessment, TSS school plan) and individual members (e.g., TSS Specialist Certification).

Model Implementation

The National Dropout Prevention Center adjusted processes to meet the needs of school districts. For example, regional model adjustments were necessary due to the large number of participating districts (16), the location of the participating schools (rural context), the expertise capacity of the AIU8 leadership team, and COVID-19 pandemic-related restrictions. Well-planned training, tools, and technical assistance supported the needs of CATs in the participating school districts.

Trainings

Essential CAT training included NDPC Trauma-Skilled™ Institutes and supplemental professional learning opportunities presented collaboratively by the NDPC and AIU8. Trainings were held via virtual Zoom format and then in-person as COVID-19 restrictions eased. Staff training opportunities were offered via recorded video(s), Zoom conferencing, and live in-person events.

Tools

In response to project/CAT needs, complementary support resources were available for easy access in the shared Google Drive. This included a variety of tools to support the five steps of the NDPC TSS Model, as listed in Table 2. Additional resources were also included.

| Support Category | Resource Type | Resource |

| TSS Model Step 1 | CAT Leadership Resources | - Milestone Tool - CAT Member Guide - Lead Team Member Guide |

| Assessment Surveys | - Trauma-Skilled™ Readiness Assessment Survey Message & Link - Student Resilience Survey Message & Links - Student Resilience Survey Return Data Sample - Sample Student Survey Permission |

|

| Staff Training Materials | - Staff Training Log with NDPC Training Links - IU8 Staff Training Intro PowerPoint & Video (3.5 min.) - Trauma-Skilled™ Schools Model Workbook (download in Step 1 Training) - School Location Key - Purposeful Practices Guide & Planning Tool - Staff Training Check- In (AIU8) |

|

| PR Tool Kit | - NDPC Intro Video (12 min.) - AIU8 Video Promo (7 min.) - Trauma-Skilled™ School Safety Rural Network One Pager - CAT Announcement - Student Letter Announcement (Elementary & Middle/High School) - Family Newsletter |

|

| TSS Model Steps 2, 3, 4 | Assessment Tool | - Individual Skills Assessment Tool - Staff Self-Care Assessment Tool |

| Planning Tool | - Trauma-Skilled™ Schools - Plan Sample Condensed Plan - Cultural Adjustment Worksheets & Samples |

|

| TSS Specialist Certification | - Certification Brochure - Narrative Component of Application - Exam Study Guide Video - Link to TSS Exam |

|

| TSS Model Step 5 | Assessment | - Implementation Assessment |

| Additional Resource Folders | CAT supports | - Individual District Folder - CAT Institute - CAT Shares - Communication follow-up - COVID-19 Support - Social & emotional learning - Training Recordings - Trauma Resources - Virtual Support Network Recordings & Resources - Wellness |

Technical Assistance

General and customized technical assistance opportunities were provided as needed for CATs and participating districts. In-person support was initially intended, but COVID-19 pandemic restrictions mandated shifts to virtual support avenues. As restrictions eased, in-person opportunities were again offered. Most districts continued to rely on ongoing virtual support as it allowed for greater levels of participation and more flexibility for busy staff members. Communication via email/phone was also effective in troubleshooting and providing a consistent source of information and support for CATs.

Project Successes

Though the COVID-19 pandemic environment offered numerous challenges to project implementation, key successes support the collaborative regional model as a promising practice for building capacity in rural school districts. During the two-year project period:

- 21 school districts participated in a project orientation session and agreed to join the Trauma-Skilled™ School Safety Rural Network, with only 1 leaving the project because of COVID-19 impact circumstances.

- 20 school districts formed catalyst action teams (CAT) that ranged from 4-9 members who completed (either virtually or in-person) the 2-day Trauma-Skilled™ Training Institute hosted by the National Dropout Prevention Center.

- 15 CATs completed the NDPC Trauma-Skilled™ Readiness Assessment (pre-test) for their targeted school(s).

- 1,181 school staff completed Step 1 of the NDPC Trauma-Skilled™ Schools Model training on The Impact of Trauma & Stress on Learning & Behavior.

- 494 school staff completed Step 2 of the Trauma-Skilled™ Schools Model training on Building a Culture of Resilience.

- 309 school staff completed Step 3 of the Trauma-Skilled™ Schools Model training on The Acquisition of Skills.

- 9 district CAT teams developed a building-wide Trauma-Skilled™ Schools Plan to include interventions for making intentional shifts in school culture by fostering student resilience through Trauma-Skilled™ initiatives as well as plans to support staff skills development.

- 22 individuals on CATs attained the NDPC Trauma-Skilled™ School Specialist certification.

- 4 AIU8 employees attained the NDPC Trauma-Skilled™ School Specialist certification.

In addition, AIU8 created a video to share the story of the project with communities and stakeholders, showcase the importance of addressing trauma in school environments, and to highlight CAT member testimonials. The video is available at https://vimeo.com/557001242.

Project Challenges

In implementing the regional capacity-building model, project leadership had to address several challenges. Among the most noteworthy were

1. Limited school district resources (i.e., time & personnel). In response, AIU8 offered CATs flexible meeting times, and online access to recordings of training and virtual network meetings.

2. Priority issues within districts (e.g., COVID-19, staffing emergencies). In response, AIU8 offered a flexible implementation timeline and increased customized support for individual school districts, with the understanding that issues of priority would arise, especially during a pandemic.

3. Limited communication within the CAT (i.e., low level of interaction or meeting time among CAT members and from CAT to AIU8). In response, the AUI8 project manager used consistent communication channels (e.g., email) to motivate team members and clarify their understanding of the requirements for Trauma Skilled™ Specialist certification.

4. Overwhelmed feelings of CAT members and heightened levels of stress among staff experiencing “one more thing to do” at school while navigating a pandemic crisis. In response, during virtual network sessions and offering technical assistance, AIU8 intensified its focus on team and school staff self-care strategies and the importance of encouraging/allowing self-care opportunities for school staff whenever possible. The virtual network proved highly motivational and valuable for CATs to share personal and district experiences in initiating staff and student self-care strategies.

5. Creation of new processes for Trauma Skilled™ Schools Model as a regional capacity-building focus instead of district/school focus. In response, the NDPC worked with AIU8 leadership to conduct evaluative reflection sessions to identify the tools and supports most needed to accommodate the regional model design and implementation.

Project Lessons Learned

Six key lessons learned in developing and implementing the regional model include:

1. Level of interest and or energy demonstrated by CAT leadership was reflected in team/district level of success, (varying from active pursuit of project objectives, pause in effort, or stagnation);

2. Focus on manageable “next steps” (one or two at a time) seemed to ease anxiety and increase the comfort of engagement of CAT members, rather than exposure to the overall implementation process (especially during the COVID-19 pandemic);

3. Investment in staff member well-being was a valuable starting point for school-wide efforts toward intentional culture shifts. District leaders who recognized and honored staff member needs for supportive care (i.e., self-care and extrinsic care), connection, and belonging, and who acted in support of those needs, established a strong foundation for model implementation.

4. Offering customized and flexible implementation options to districts (while maintaining fidelity of the Trauma-Skilled™ Schools Model and Trauma-Skilled™ Specialist Certification process) was essential to CAT/district’s ability to fulfill project objectives.

5. Facilitating collaboration among CATs in the virtual network encouraged sharing and offered valuable support.

6. Facilitating reflection sessions for the IU and NDPC leadership team early in the project period and maintaining ongoing communications fostered relationships and efficiencies in developing and implementing the regional capacity-building model.

Summary and Model Scale-up

Though slowed by pandemic circumstances, by the end of the Project, numerous CATs were positioned to carry out activities for schools to implement the NDPC Trauma-Skilled™ Schools Model. At the end of the Project, many school districts also functioned more like partners rather than clients of the AIU8. The AIU8’s focus on trauma-impacted students, in partnership with the NDPC, occurred at a time when the school districts were responding to the “well-being” needs of all persons in a school. AIU8 provided essential facilitation skills for the virtual network, but it was the willingness of each CAT to contribute time, share resources, and build relationships that evolved the network into a sustainable support for the CATs in the region. Also, for example, some CATs developed resources for sharing with other CATS, such as infographics as visual representations of “purposeful practices” implemented in their schools.

Figure 4 provides an infographic that summarizes the AIU8 regional model for building Trauma-Skilled™ schools leadership capacity in a rural region. The IU and NDPC form a collaborative partnership that targets member school districts for engaging the capacity-building strategy. Each participating school district forms a Catalyst Action Team (CAT) composed of 4-9 members, or more if necessary. CAT members participate in NDPC TSSM training and then select the school(s) as the site(s) to conduct key activities. These activities apply competencies learned in the training and warrant progress toward the NDPC TSS Specialist certification.

The AIU8 facilitates a “blended” (mostly virtual) network for participating CATs to share ideas, successes, challenges, and lessons learned. Individual CAT members and appropriate AIU8 staff attain the certification by supporting elements of the Trauma-Skilled™ Schools Model, participating in the network, submitting the NDPC application with a satisfactory narrative, and passing the NDPC Trauma-Skilled™ certification exam. Consequently, the region achieves the capacity to implement the NDPC Trauma-Skilled™ Schools model. The names and photo/bios of those attaining the certification are added to the NDPC TSS database with access to key resources in the nation’s only Trauma-Skilled™ certification program.

AIU8 and NDPC personnel presented project accomplishments and model elements at national conferences of the Association of Educational Service Agencies (AESA), the National Dropout Prevention Center (NDPC), and the National Rural Education Association (NREA). Discussions with conference participants prompted AIU8 leadership to recognize the potential of the regional model for school districts in other rural areas. Consequently, AIU8 approached legislators in the AIU8 region and PA Department of Education personnel to share information on the model. Moreover, leadership of the NDPC and Successful Practices Network revised their partnership effort with AUI8 to support piloting scale-up with another Intermediate Unit in PA.

Formed as the Trauma-Skilled™ Schools Collaborative Network, AIU8 selected a partner IU to focus on scale-up support. The partner IU selected its site coordinator, who is mentored by the program manager of the original AIU8 project. The scale-up partner IU has established a CAT in seven of its school districts. Approximately 60 additional CAT members have participated in training offered by NDPC as an in-person Trauma-Skilled™ Institute.

With the support of the AIU8 mentor, NDPC personnel, and the partner IU’s site coordinator, members of CATs have initiated activities toward the attainment of specialist certification, development of a Trauma-Skilled™ Schools plan for targeted district schools, and implementation of “purposeful practices” of the TSS model. Moreover, the AIU8 is developing a “playbook” type document that provides clarity for partners or potential partners on the many processes, tools and supports associated with model implementation.

Districts in the original AIU8 project continue to have access to ongoing training and support to advance the implementation and sustainability of the TSS model. Currently, the new Collaborative Network supports seven districts in the partner IU and 16 districts of AIU8.

Leaders of educational service agencies interested in the regional capacity-building model to create trauma-skilled schools in member districts should contact Dr. Tom Butler, AIU8 Executive Director via email at TButler@iu08.org or 814 940 0223 ext. 1300.

Authors:

Hobart L. Harmon, PhD, Leader of Strategic Advancement, Appalachia Intermediate Unit 8 and Senior Research Associate, Kansas State University. He can be reached by phone at 540-421-5011 and by email at hharmon@shentel.net.

Sara Quay, Trauma-Skilled School Safety Rural Network and Project Manager. She can be reached by phone at 814-502-5134 and by email at squay@iu08.org.

Jennifer Anderson, Director of Professional Learning & Organizational Development and

Regional Coordinator for Safe Schools & School Climate L2. She can be reached by phone at 814-940-0223 x1320 and by email at janderson@iu08.org.

John Gailer, Director of Professional Services, National Dropout Prevention Center. He can be reached by phone at 518-723-2063 and by email at jgailer@dropoutprevention.org.

Thomas A. Butler, PhD, Executive Director, Appalachia Intermediate Unit 8. He can be reached by phone at 814-940-0223 x1300 and by email at TButler@iu08.org.

References

Gailer, J., Addis, H., & Dunlap, L. (2018). Improving school outcomes for trauma-impacted

students. Anderson, SC: National Dropout Prevention Center.

Gillen, A. L., Grohs, J., Matusovich, H. M., & Kirk, G. R. (2021). A multiple case study of an inter-organizational collaboration: Exploring the first year of an industry partnership focused on middle school engineering education. Journal of Engineering Education, 110(3), 545-571. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20403

Harmon, H. L. (2017). Collaboration: A partnership solution in rural education. The Rural Educator, 38(1), 1-5. https://journals.library.msstate.edu/index.php/ruraled/article/view/230/210

Johnson, J. D., & Harmon, H. L. (in press). Video documentation of the international rural school leadership project: A retrospective case study of university-school-community collaboration. In R. M. Reardon & J. Leonard (Eds.) School-University-Community research in a (post) covid-19 world. Information Age Publishing.

Kolbe, L. J., Allensworth, D. D., Potts-Datema, W., & White, D. R. (2015). What have we learned from collaborative partnerships to concomitantly improve both education and health? Journal of School Health, 85(11). https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12312

Miller, P. M., Scanlan, M. K., & Phillippo, K. (2017). Rural cross-sector collaboration: A social frontier analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 54(1), 193S-215S.

Miller-Stevens, K., & Morris, J. C. (2016). Future trends in collaboration research. In J. C. Morris & K. Miller-Stevens (Eds.), Advancing collaboration theory: Models, typologies, and evidence (pp. 276-287). Routledge.

Moots, S. C. (2021). Preparing educators to serve trauma-impacted students through the trauma skilled schools model: A research brief. Developed for presentation at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association.

Morris, J. C., & Miller-Stevens, K. (Eds.). (2016). Advancing collaboration theory: Models, typologies, and evidence (pp. 43-64). Routledge.

Nichols, L. M., Goforth, A. N., Sacra, M., & Ahlers, K. (2017). Collaboration to support rural student social-emotional needs. The Rural Educator, v38(1), 38-48. https://doi.org/10.35608/ruraled.v38i1.234

Peterson, J., & Densley, J. (October 9, 2019). What school shooters have in common. Education Week, Vol. 39, Issue 08, Page 20. Retrieved from https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2019/10/09/what-school-shooters-have-in-common.html

Polk, L. (2021). Educational service agencies: Review of selected/related literature. Perspectives Journal. Retrieved March 12, 2023, from https://aesa.cms4schools.net/blog/?p=380

Reardon, R. M., & Leonard, J. (Eds.). (2018). Innovation and implementation in rural places: School-university-community collaboration in education. Information Age Publishing.

School Social Work Association of America (2012). School social work services. Retrieved September 10, 2019 from https://www.sswaa.org/school-social-work.